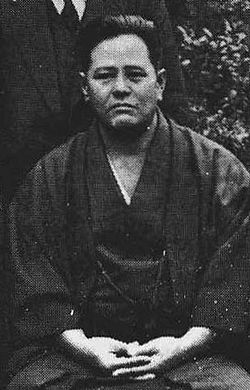

Chōjun Miyagi was a pivotal figure in the history of Okinawan karate, renowned as the founder of Gōjū-ryū. Born on 25 April 1888, in the Higashimachi district of Naha, Okinawa, his original given name was Matsu. This was later changed to Chōjun in 1893, after his father’s death, when he was adopted into his uncle’s prosperous business family. His family was involved in foreign trade with Fuzhou, China, and was among the wealthiest in Naha. Miyagi was described as physically strong and fond of sports, earning a reputation as an “unruly youth”. Despite his later wealth, the war led to the destruction of his assets and fortune.

Miyagi’s martial arts journey began at a young age. When he was ten or eleven, he started training with a Tomari-te practitioner named Aragaki Ryuko, who, in 1902, introduced the promising young student to Higaonna Kanryō, who became his principal teacher. Miyagi continued to train diligently under Higaonna Sensei until his teacher’s death in 1915. It is worth noting that Kyoda Juhatsu, a fellow student, was a year older than Miyagi and began training with Higaonna a year earlier, making him Miyagi’s “sempai” (senior student).

Miyagi’s training with Higaonna was interrupted for a two-year period (1910-1912) while he completed his military service in Miyakonojō, Miyazaki. During this time, as a non-commissioned officer in the army medical corps, he studied judo and acquired knowledge of anatomy and physiology, which he later incorporated into his unique warm-up or conditioning exercises, junbi undo.

Following Higaonna’s passing, Miyagi travelled to Fuzhou, China, in May 1915, to deepen his understanding of martial arts, just as his teacher had done. During this first trip, he visited the grave of Ryū Ryū Ko, Higaonna’s teacher, and trained for two months with one of Ryū Ryū Ko’s students, an elderly gentleman who had been a junior student alongside Higaonna. Through these sessions, Miyagi confirmed that the nine kata he learned from Higaonna were indeed the same ones taught by Ryū Ryū Ko. He also learned the Chinese characters for these kata. Miyagi made a second trip to Fuzhou in 1916 with his Chinese friend, Wu Xiangui (Go Kenki), an exponent of Fujian White Crane quanfa, during which he studied local Chinese martial arts. It was during this second trip that he observed the Rokkishu (a set of hand exercises), which he adapted into the Tensho kata.

Miyagi was born into a wealthy merchant family and worked in their family business, which engaged in foreign trade with Fuzhou. However, he dedicated most of his time and passion to karate, often neglecting sleep and food in his pursuit of knowledge.

Miyagi played a crucial role in standardising and popularising karate-dō. His greatest achievements were in the popularisation and organisation of karate teaching methods. He began teaching karate in public institutions, becoming an instructor at the Prefectural Police School dojo in 1929 and later teaching at the Naha Courthouse, the Prefectural Physical Culture Association, and the Prefectural Teachers’ Training College. He also lectured and demonstrated karate at various Japanese universities on the mainland. In 1938, he was nominated as the Karate Instructor for the Okinawa Prefecture Teachers College. After World War II, despite personal losses and a “smashed homeland,” he continued teaching, notably to the Ryukyu police.

In 1930, Miyagi officially named his style Gōjū-ryū, drawing inspiration from a passage in the Bubishi text: “The way of inhaling and exhaling is hardness and softness” (Ho go ju donto). This name was chosen to reflect the blend of hard and soft techniques, with an emphasis on breathing, making it “an ideal name”. This official naming was vital for karate’s acceptance within the larger Japanese society, especially by the Dai Nippon Butokukai, a martial arts regulatory body. In 1933, Gōjū-ryū was officially recognised by the Butokukai, and in 1936, Miyagi was granted the Kyoshi title, the first karate teacher to receive such an honour, elevating karate’s status alongside judo and kendo.

Miyagi believed that karate should extend beyond mere fighting techniques. He stated that “training the body and mind in karate results in the cultivation of a strong character and an indomitable spirit”. His curriculum included character development and a broader education, inviting guests to the dojo to lecture on calligraphy, music, literature, poetry, and medicine. He famously advocated for the principle “karate ni sente nashi” (“in karate, there is no first attack” or “no aggression”), advising students to avoid confrontations altogether and emphasising a “humble attitude coupled with hard practice”.

Miyagi’s contributions to kata development were profound. He synthesised what he learned from Higaonna and his research in China. He developed junbi undo (warm-up exercises) and structured the Gōjū-ryū syllabus to include hojo undo, kihongata (fundamental kata like Sanchin and Tensho), kaishugata (eight other Gōjū-ryū kata), and kumite renshu (sparring training). The popular Geki Sai Ichi and Geki Sai Ni kata were not developed until 1941. While some sources suggest his experience with Miao Xing inspired Geki Sai kata, this is disputed. Miyagi was “obsessed with sanchin kata,” believing it to be “the core of all martial teaching”. He taught sanchin as a moving meditation, emphasizing precise control, forceful breathing, and full-body tensing at impact. He also revised and further developed Sanchin and created Tensho, considering them the essence of Gōjū-ryū. At the end of his life, Shisochin was his favourite kata.

Miyagi taught a total of twelve kata that form the basis of modern Gōjū-ryū: Sanchin, Gekisai-ichi, Gekisai-ni, Saifa, Seiyonchin, Shisouchin, Sanseiru, Sepai, Kururunfua, Sesan, Suparinpe, and Tensho. Notably, his senior, Kyoda Juhatsu, learned the Sanseiryu kata directly from Higaonna when Miyagi was serving in the military, a fact Kyoda held with considerable pride.

Chōjun Miyagi attracted many dedicated students who would go on to become prominent masters themselves. These included Eiichi Miyazato, Meitoku Yagi, Seiko Higa, Jinan Shinzato, Gogen Yamaguchi, Anichi Miyagi, Shuichi Aragaki, Seikichi Toguchi, Keiyo Matanbashi, Jinsei Kamiya, Genkai Nakaima, Tatsuo Shimabuku, and Koshin Iha.

Miyagi’s teaching methodology was unique; he individualised instruction based on each student’s needs and abilities, believing that “no two students were exactly alike”. He never awarded ranks during his lifetime; the first Gōjū-ryū black belts were awarded only after his death in 1953.

In his final years, Chōjun Miyagi suffered from grave illness, which limited his ability to teach effectively. After World War II, he faced immense personal tragedy, including the loss of three of his children, and his homeland was left devastated under US military rule.

Chōjun Miyagi passed away on 8 October 1953, at the age of 65, from a cerebral haemorrhage, having had his first heart attack in 1951.

His passing left a void in the Gōjū-ryū community, as he had not officially named a successor. Several senior students claimed succession, but the Miyagi family recognised Eiichi Miyazato, who continued to teach in Miyagi’s garden dojo and later established the Jundokan. The prominence of Kyoda Juhatsu as Higaonna’s direct disciple led some senior Gōjū-ryū students to ask him to succeed Miyagi; however, his condition to rename the style “To’on Gōjū-ryū” to honour Higaonna was rejected.

Chōjun Miyagi’s enduring legacy is evident in his instrumental role in transforming karate from a secretive combat art into a systematised martial way accessible to the public and recognised worldwide. His “staggering” life and legacy continue to shape Gōjū-ryū practitioners globally, with his emphasis on character development, modesty, and hard training remaining core tenets. The enduring popularity of his style and the widespread recognition of his principles stand as a testament to his profound impact on the martial arts world, even inspiring fictional characters like Mr. Miyagi in The Karate Kid.